John Walker on his use of/interest in/thoughts on text in his paintings:

’In college, text was taboo to put in paintings. But I was looking around at what was going on. The first paintings with text that I noticed were David Hockney paintings. And then Pop art burst onto the scene towards the end of school. David Hockney was considered radical. Jasper Johns, early Rauschenberg. And I took notice. I felt I couldn’t say enough with the figure so I started including a few words. Like HELP.’ ‘At the same time I was trying to find a way to be an abstract painter about figurative issues. I was trying to invent non-figurative forms to make my figurative forms obsolete.’ ‘I made a series of large paintings that were comics — with figures and bubbles with words. Eventually I turned the figures into abstractions with bubbles. Then I got rid of the bubbles altogether. I was left with abstractions and words. These words became the titles of the paintings, like: ANGUISH. TOUCH. These titles are very figurative.’

‘I began showing my work and getting more involved in other art being made — the art world, if you will. I saw a Bruce Nauman painting that was a list of words. It was the first piece of art in a gallery I ever wanted to own. I couldn’t afford it.’

‘Historically, I grew up in the English countryside. There was text on the walls in churches. During the reformation, the Catholic art was destroyed and thrown out and then replaced, a lot of it replaced by biblical text painted on the walls of the churches. Painted with tempera paint. Bits and pieces were flaking off over time. These were poignant things that were beautifully painted. These words were there, and though at that time I couldn’t call it painting, these were obviously an influence. I thought about these images and thought maybe this kind of overlapping of text could be included in my paintings.’ ‘I saw the Motherwell painting Je Taime, blue and yellow, painted in 1965.’

‘My antenna was up, and I was used to seeing things. I saw Jasper Johns letter paintings and number paintings and they stayed with me.’

‘I had children. My daughter Claire, when she was very young, made me a birthday card using my own oil paint. She wrote FOR YOU across a folded piece of paper. On her birthday, I made one back for her, and wrote FOR YOU across the canvas. I got such a thrill out of touching FOR YOU. That was the first time I realized it doesn’t mean a thing until you touch [paint] the word. That’s the justification, the act of painting.’

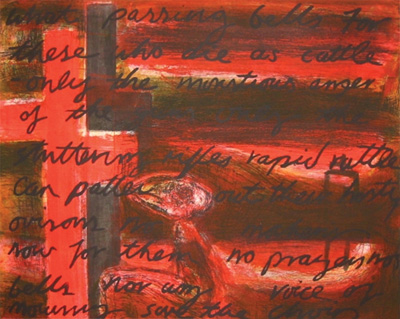

‘When I was painting about my father and World War I, I began using imagery from poets like Wilifred Owen and poet/painter David Jones. Owen and Jones reminded me of how my father talked. For a long time I just painted their poetry and it only worked when I touched the words. I’d been there. I’d painted it. Touching imbued the text with verbal pain as well as visual pain. Readability doesn’t matter.’

‘In my Oceana series I began to integrate passages from the Bible. People kept asking me if my Alba shape was a reference to a door, and it was not. I’ve found it interesting that in the Bible, Christ was asked certain things which he denied. I tried to make oblique references to this.’ ‘At the end of the day if it doesn’t work with a brush in my hand it is no good.’

‘And then at some point I couldn’t start a painting unless I had some writing.’

‘I began painting the Maine landscape and in Maine I would encounter a lot of signs that were hand painted for people selling stuff on the side of the road — like BLUEBERRIES or CLAMS. I’d see these signs against the Maine landscape. I began to use these words as starting points, as a way to begin — just by painting the word BLUEBERRIES or the word CLAM across my canvas.’

In the 60’s John was making text paintings on the wall—he’d first prime the wall with chalkboard paint, write on the chalkboard, wipe it clean, and then write again, and so on. Ultimately these paintings didn’t feel like painting for him, they felt like career moves, and he became uncomfortable. He ended up using these wall paintings as a move to get back into painting rather than to get out of painting. There was a show of these wall paintings and actual chalkboards at MOMA in 72 or 73 — John can’t remember.

On choosing what text can go in a painting: ’Ultimately, if it works formally, then it’s fine in a painting.’

John Walker, Passing Bells, 2000. 5 plate color etching and aquatint.

’It’s a highly selective process, I have to care about the words. But if the words don’t paint, then I can’t use them, either. Even from a poet you have to select the words. I am so close to words that it hurts sometimes to paint words. I’m such a romantic. I can paint the Bible, blueberry signs. I’ve tried, on a number of occasions, to buy a blueberry sign on the side of the road in Maine — painted in a purple blue with wonderful blue dots underneath the word BLUEBERRIES. I’ve offered $250 for one of these handpainted signs on wood or cardboard but these guys won’t sell them. There’s an immediacy to these blueberry signs. They’re pure. They’re direct. They’re raw. Something you see in great art.’ ‘People have said you can’t use words in painting. Purists have said this. But ‘pure’ art has been bastardized for a long time now — cubists used words, in the 50’s Kaprow, Rauschenbeg, assemblage — all this roughed up painting and bastardized it, introduced other media into painting and it all became problematic.’ ‘I’m a sentimentalist. I’m a sucker for hallmark cards. I’m a sucker for anything that enriches people directly. Like country and western music. Or the opera. Opera contains all of the arts, comes right at you and hits you in the heart. I’m a romantic and a sentimentalist.’ ‘Art can get too arrogant. When you worry about your audience or whether or not you have an audience at all.’